Horror cinema has been a self-aware genre for at least twenty years, if you count 1996’s hyper-meta slasher flick Scream as the start of the era—longer if you take into account Abbott and Costello meeting Frankenstein in 1948 or Evil Dead II parodying its predecessor in 1987. But in recent years, horror’s tendency toward metafiction has become even more granular. Whereas the classic franchises commented on the genre of horror itself, modern films are looking within their own bodies of work. This year sees two “modern classic” franchises reinvent themselves: Both Blair Witch (2016) and Rings (2017) reference their source material—that is, their original films—by treating them as “creepypasta,” the next evolution of urban legends for those who grew up on the internet.

But first, let’s look at how we told scary stories in the ’90s. Fed on a steady diet of ’80s slasher films, Scream‘s teen protagonists deconstructed and lampshaded the horror-movie tropes in which they were caught during Ghostface’s rampage, to the point that there were few surprises—you could “game” the horror movie when it happens to you, was the lesson. What’s more, as the real killers demonstrate with their preplanned alibi, you could even make the case that consuming that much horror drives you to pick up a knife yourself.

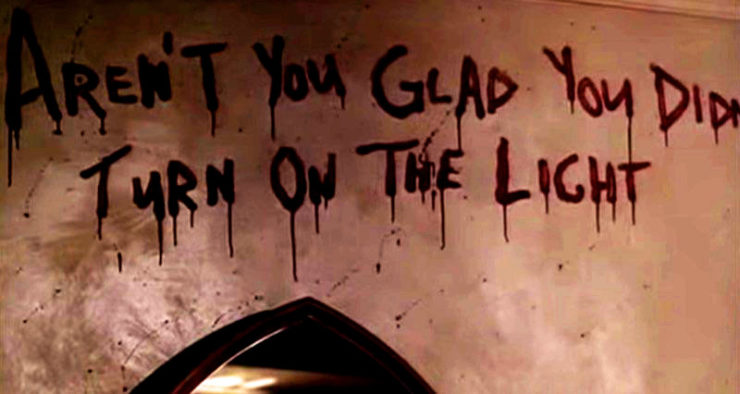

Just like Ghostface, the killer in 1998’s Urban Legends taps into a healthy reserve of horror for their killing spree—but instead of tropes, it recreates the chilling urban legends shared among this same generation (a few years older, now in college). Each murder is modeled after a story, down to the pervasive ambiance and the grisly details: the creepy gas station owner scaring off a poor girl when he’s trying to warn her about the backseat hitchhiker armed with an axe; the unlucky boyfriend strangled on the roof of the car, killed when his panicked girlfriend speeds away and leaves him dangling; the girl who is killed in the dark under the guise of a kinky encounter, only for her roommate to see written in blood the next morning Aren’t you glad you didn’t turn on the light? And it’s all revenge for a botched attempt at acting out an urban legend, which ended with an innocent guy dead.

Urban Legends and Creepypasta

Urban legends, as I grew up with them (in the ’90s and early 2000s) via late-night Snopes reading on the family desktop computer and wide-eyed retellings at sleepovers and sleepaway camp, were spread through word of mouth and then the internet, or vice versa. By contrast, creepypasta is less an established legend and more an immersive, mutable, ongoing story. Aja Romano’s primer on The Daily Dot, despite being four years old, is the best resource I’ve found for defining its origins and key characteristics:

- Creepypasta came out of “copypasta”, chunks of text that can be easily copied/pasted without attribution.

- However, creepypasta sticks with you because of its eerie content: “their horror often enhanced by their brevity, their journal-style format, or their casual, ‘here’s a creepy thing that happened to me once’ narrative style.”

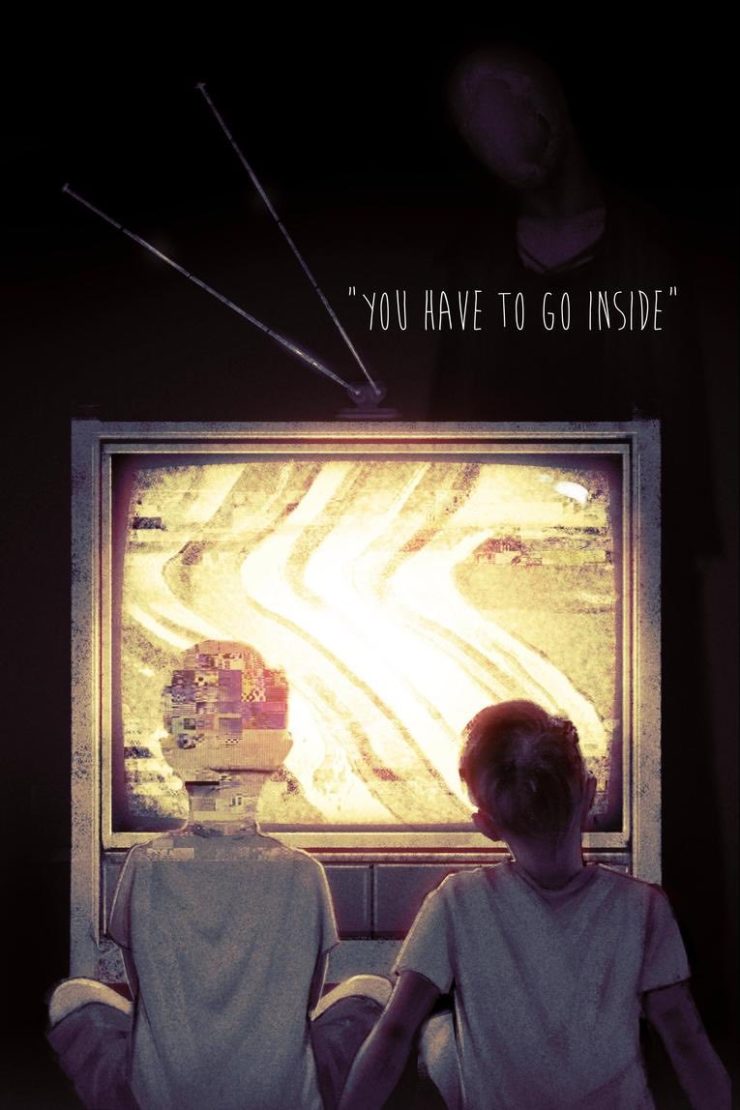

- Mirroring urban legends, creepypasta stories obsess over the potential evils lurking within modern technology, especially those related to communication: a TV set that leads into another dimension, a cursed video game, a malignant computer file.

- Romano also writes: “Creepypasta also often reveals a sense of deep distortion of reality, the kind of just-slightly-off view of the world that only comes from the collective imagination of 4channers, Something Awful goons, redditors, and others who’ve found themselves glued to their computer at 3am reading about Mothman, Chupacabra, or other modern-day monsters.” Like, say, Slender Man:

David Cummings, narrator of the NoSleep podcast, inspired by Reddit’s r/nosleep, hits upon the most compelling aspect of these kinds of stories, in a Den of Geek piece on the history of creepypasta:

“A lot of the stories are really well-crafted and well-told, but they’re not necessarily literary. You don’t get these grandiose descriptions. They’re breatheless [sic]. ‘Oh my God, I just ran out of my friend’s house and I have to tell you what happened.’ There’s an immediacy and a believability.”

The goal of each story on the podcast and the subreddit is to be scary, personal, and above all else: believable.

There is a near fanatical devotion to the suspension of disbelief on r/NoSleep that has seemingly created the prototype for nearly all internet scary storytelling. Among the extensive rules and guidelines for the site is the phrase, “Suspension of disbelief is key here. Everything is true here, even if it’s not. Don’t be the jerk in the movie theater hee-hawing because monkeys don’t fly.”

Cummings also makes a distinction between generic creepypasta and these detailed stories, which he likens to campfire tales, but for the sake of this article, I will refer to all of them under the catch-all name creepypasta.

This suspension of disbelief doesn’t exist when you’re reading an email chain letter or Snopes entry. While listeners to an urban legend can egg on the storyteller with their bated breath and whispers of and then what?, r/nosleep commenters and other creepypasta enthusiasts actively immerse themselves in the story. The original posters (OPs) share updates and follow-ups, turning one-offs into multi-chapter sagas, and readers clamor for more, demanding to know what happened to the narrator or throwing in their own experiences that use the yes and rule of improv to strengthen the strands of the story. Instead of trying to debunk the story, they accept it as “truth” no matter how implausible. With everyone buying into the “authenticity” of these creepypasta stories, you remove the dimension of trying to step outside of the story by disproving it. Everyone is invested, which makes it ten times scarier. Once you forwarded the scary chain letters to the next victims, they were out of sight, out of mind—with creepypasta, even lurkers are participants.

Rings

The Ring franchise best exemplifies this shift in storytelling. The Ring, the 2002 American remake of the 1998 Japanese horror film Ring, turns the chain letter into a cursed VHS tape: Once you watch the surreal, disturbing film, you’re haunted by Samara for seven days, until she comes staggering out of your television… unless you make a copy of the video and force someone else to watch it, passing along the curse. While The Ring Two (2005) was an uneven sequel, the supplementary short film Rings introduced a fascinating bit of worldbuilding: As more and more people figure out the secret to surviving Samara’s curse, the number of survivors grows. In turn, a subculture arises: “rings,” groups of people who have watched the video and challenge themselves to get to seven days—fighting the physical and psychological trauma of Samara’s haunting—before indoctrinating others. In a prescient bit of storytelling, screenwriter Ehren Kruger channels YouTube—which would become popular that year—by having members of the rings record and document their experience pushing the seven-day deadline.

While Rings is a prequel to The Ring Two (the former leads right into the opening scene of the latter), some have theorized that it’s also the source material for the next installment Rings, due out in 2017—not least because they share the same name. In fact, it was Vulture’s writeup of the first Rings trailer that first gave me the inspiration for this piece: Instead of the VHS tape, they observed, the infamous video can now be played on infinite screens, from an email attachment to in-flight entertainment. What’s more, the official synopsis corroborates these theories: A young woman named Julia become concerned when her boyfriend begins delving into the rings subculture, curious about the video’s origins. In trying to deter him from the same fate others have fallen to, she stumbles upon the horrifying knowledge that there is a “movie within the movie” that no one has ever seen before. Julia apparently becomes a key figure, because as you can see from the trailer, Samara takes a special interest in her:

It’s difficult to truly parse out the differences between urban legends and creepypasta. For one, they both rely on the stories getting retold or duplicated. But with the former, it’s not an identical copy; details are added or dropped in a game of Telephone, and the narrator’s relationship to the characters (“my brother’s girlfriend/old classmate/boss”) changes as a new storyteller relates the tale. Urban legends was always more traditional storytelling; there’s a level of detachment even if you claimed that the story in question really happened—because it always happened to someone else, however many degrees removed.

But because creepypasta is told in the first-person, no matter how many times the same creepypasta story link gets sent around, the narrator remains the same. In Rings, Samara tries to reincarnate herself through Julia: In addition to the quintessential Ring experience of yanking a massive hairball out of her throat, Julia has burn marks on her hands that spell out “rebirth” in a foreign language, while her skin is slowly peeling away. No matter how many sets of eyes are fixed on the video, no matter how many times the horror is copied and redistributed, it never stops being Samara’s story.

Blair Witch

Rings’ theatrical release has been pushed to January, but another game-changing horror franchise has already debuted a sequel well ahead of Halloween: Blair Witch, a direct sequel to 1999’s found-footage phenomenon The Blair Witch Project. (Like Rings, it’s technically the third film in its franchise, but we don’t talk about Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2: Gas Leak Year.) One, because it was awful, churned out on the heels of the first movie’s success; two, because it went super-meta, tracking a bunch of tourists who want to explore the woods after seeing the found-footage phenomenon The Blair Witch Project. By ignoring Book of Shadows, the new film re-grounds itself in a world where the Blair Witch is still a local legend—and the only footage that Blair Witch protagonist James Donahue is concerned with is the videotape from the original story—shot by his sister Heather, from her fatal foray into the woods 17 years ago.

Again, it’s a matter of proximity to the story. If the plot of Blair Witch were simply about James watching this mysterious footage of his sister’s final days, it would be an urban legend. But because James (along with his friends, a film student, and the locals who found the videotape) ventures into the woods, compelled by the slim possibility that his sister is still alive, and records the whole thing—then it becomes creepypasta.

Of course, it’s all very calculated. Heather Donahue is a real person, an actress and filmmaker who suffered professionally because of how the studio faked her death to ratchet up the “authenticity” of their found-footage horror film in a pre-social media era where that kind of hoax couldn’t be debunked so easily. Nowhere in The Blair Witch Project does Heather mention a brother; he’s clearly been retroactively written in to provide emotional grounding for the sequel. In fact, the studio doesn’t actually refer to Heather by name in Blair Witch, out of respect. It’s clear from the trailers and the film that James is going into the woods after his missing sister, but it’s never explicitly said. Furthermore, while Blair Witch delivered scares in the vein of its predecessor, it failed to replicate the multifaceted effect of The Blair Witch Project, according to Screen Rant’s review:

Where The Blair Witch Project featured a convincing and gut-wrenching depiction of real human beings crumbling in the face of physical and emotional exhaustion, regardless of the overarching supernatural storyline, Wingard’s film is populated with people and situations that exist to define the Blair Witch legend more than the cast and events at hand. Viewers gain a clearer understanding of the Blair Witch herself, and the reach of her powers, but this comes at the expense of established plot lines and relationships that go next-to-nowhere.

Emphasis mine—these thinly-drawn characters bring to mind creepypasta commenters, who play along with the narrator to keep the momentum of the story going, rather than trying to trip him/her up with logic or proof. In both cases, these franchises are effectively ignoring their hasty sequels in favor of reimaginings, after a decade or more to think on the material. By treating their original installments as creepypasta, they open up a whole new dimension of the impact that The Ring and The Blair Witch Project have on their respective universes.

Channel Zero

Then there’s Syfy’s new horror anthology series Channel Zero, which literally draws from real creepypasta as source material. Kris Straub’s “Candle Cove” taps into what is apparently a universal discomfort with ’70s-era public access television, the kind of surreal stuff you might catch on a drowsy summer afternoon and never be able to find again. Until, of course, the internet: “Candle Cove” is written as a series of message-board posts as members of a nostalgia-centric forum slowly realize that they all watched the same bizarre kids’ series, with its fourth-wall-breaking messages and disturbing violence against puppets, during their childhoods. Or did they? As their memories of the program become increasingly horrific, one of the original posters, mike_painter65, reveals an unsettling discovery: After asking his nursing-home-bound mother if she remembered the show, she said that he would just tune the TV to static and watch dead air for 30 minutes: “you had a big imagination with your little pirate show.”

Straub told Den of Geek that he never intended for “Candle Cove” to be a hoax: “[I]t’s an epistolary story in the format of forums. It had my name on it and all, but when people shared it, that all got stripped away. So as a creator I get bent out of shape about that—but as a consumer, I see the power that that had in letting the legend grow. People didn’t know if it was real or not. They still don’t.”

Now, the “Candle Cove” story makes up the arc for the first six-episode season of Channel Zero: Child psychologist Mike Painter returns to his hometown despite his traumatic memories of his twin brother’s disappearance decades before. But when more children from the town go missing, Mike discovers the terrifying link: the hypnotic, disturbing program Candle Cove.

Straub doesn’t seem to be involved beyond granting permission to screenwriter Max Landis to option the material. In a recent interview with Birth.Movies.Death., co-creator Nick Antosca—who cut his teeth on Hannibal—explains how “Candle Cove” was the core for the series, but also how much he built around it:

Because Kris’s story is not a traditional narrative—because it’s formatted as message board posts—it actually gave us more freedom in terms of adaptation. I wanted to stay true to the spirit of the story and preserve the feeling it gave me when I read it. We recreated the puppet show as faithfully as possible, and then built the world around it. The Candle Cove season is personal for me in a lot of ways, because the nature of Kris’s story required a lot of invention. The town of Iron Hill is inspired by the rural area in Maryland where I grew up. So it’s a balancing act, and a challenge—bring new ideas to the table, but honor and preserve the original story. Hannibal was good training for that.

Fangoria favorably reviewed the pilot, praising the decision of “utilizing the untrustworthy narrator, which allows the show to be flexible with its use of reality in order to provide it’s [sic] most macabre moments.”

Antosca also described the series to Collider as “almost […] like a nightmare you’d have after reading the original Creepypasta.” The end result, according to Vox, is a mix between Stranger Things and True Detective: a supernatural horror menaces the children of a small town, but rather than inspiring a ragtag group of kids to reenact Dungeons & Dragons IRL, the prevailing mood is (as the kids would say) bleak AF. It’s interesting to consider that alongside a 2014 interview with Straub, when he was just discussing the film rights with a studio and where he explained why any sort of sequel to his original creepypasta inevitably fails, when asked if any of the unofficial sequels were his favorites:

Oh man, none of them are my favorites. The reason is that they all try very hard to explain what Candle Cove is, when not knowing is why the story resonated. There’s this string of fanfics where it’s revealed that Candle Cove is the work of an old Nazi named Altman Bachmeier. You tell me why a Nazi would be hanging out in West Virginia or Kentucky in 1971, and why he’d bother making a puppet show to scare kids. I guess “Nazi” is shorthand for “the most evil thing anyone can think of.”

While I doubt that Syfy will go the same route, by this reasoning, any explanation they come up with will be entirely separate from the impact of Straub’s story. His “Candle Cove” ends with the twist about the static; there’s no need to explore beyond the bounds of the story, as the mere question of how all of these children tapped into the same nightmarish show is enough to give readers existential chills. That doesn’t mean that Channel Zero: Candle Cove shouldn’t try, only that the answer may not be satisfying for the audience who originally made Straub’s story go viral.

In lieu of a proper campfire, Natalie Zutter will link you to her favorite urban legend and creepypasta: “People Can Lick Too” and “Under or Over.” She dares you to frighten her with your favorite scary stories on Twitter.

I don’t really think that the first person narration is that much of a distinguishing quality as to call creeypastas something different to urban legends. I just think they’re a subcategory. Of course, that’s my opinion, and I thank you for directing me to Candle Cove. Puppets and pirates make me happy.

Candle Cove! That just made me really happy, Candle Cove is one of my favorite Creepypastas. I remember thinking awhile back that some kind of adaptation could be really cool (although my thought at the time was some kind of video game), and I really hope this one turns out to be good.

My other favorite Creepypasta is Anansi’s Goatman story. It’s really good at creating a sense of paranoia, and although it may not be pee-your-pants scary, it is incredibly disconcerting. At first it does have the feel of the traditional camping in the woods type scary story, but it takes it in a somewhat different direction than others do. The typos and occasional grammatical errors actually work in the story’s favor–it really does feel like an email or something someone typed on a message board. It also works as excellent proof that there doesn’t necessarily have to be a body count for a story to give you the creeps.

In 1997 I could very easy been the forerunner to this phenomenon; as I wrote the short story that invaded Clive Barker’s website in 2000 when a piece I wrote when I was 20. I also then wrote an ultra-violent short story called A Cemetery Dream which the House of Pain E-Zine editor knew about from my appearance on House of Andromeda. When I submitted Gruesome Cargo to TOR; I was returning to my intense ultra violent roots as a horror author.

I toned it back in the mid-2000s as I had a readership that was much younger when I came to FictionPress, as in 2002 when Kealan Patrick Burke emerged on The House of Pain with The Clause. (I have made an expose public a few years back called “Boycotting Truth.”) I had revised parts to include the Chicago Tribune article about the case that I remembered parts of the dialog as the conversation in the back of a taxi going through Carol Stream became a candid chilling admission of both involved in the conversation. I introduced a piece that was the creative nonfiction successor to The Tell-Tale Heart when I was 25 turning 26.

In 2004 I introduced the horror nasty House of Spiders, the short story that’s the bane of slashdom, and the science fiction narrative Lake Fossil as a debated story that was discussed by Fan History’s lady as I outed a known fan fiction writer who actively screwed me over.